Project Manager/Author: Matt Wong | Darius Dastur | Tanner Dekock

Introduction

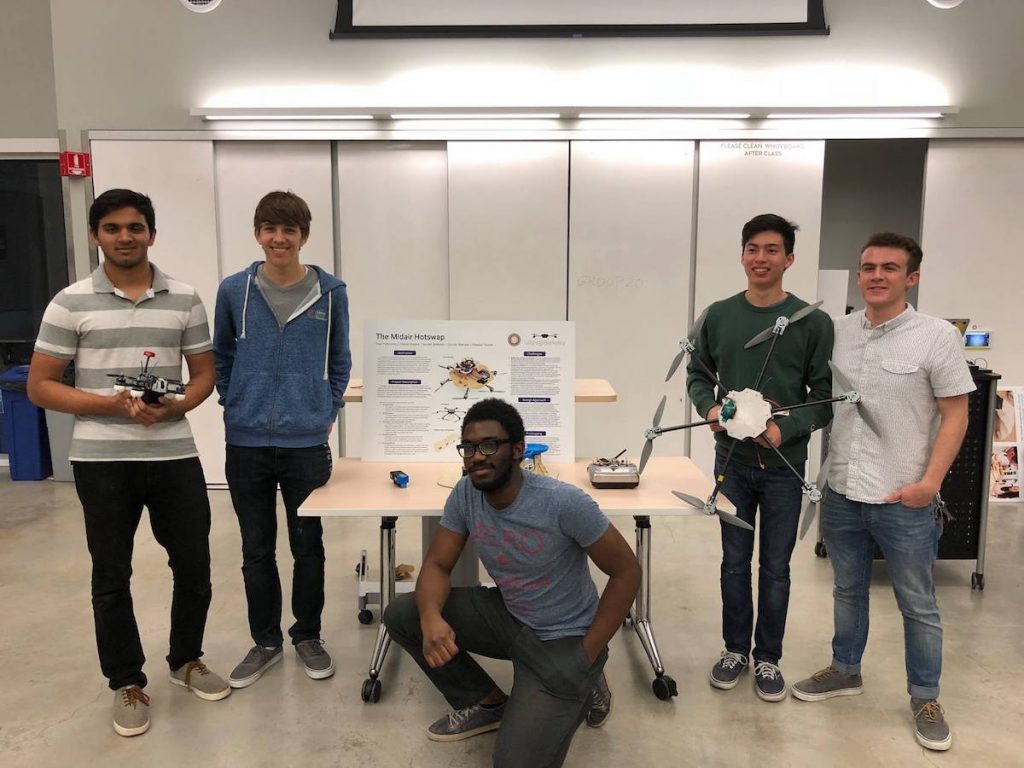

I began the Midair Hotswap project at the start of my Sophomore year as a Project Manager. We started with about 12 people and over the course of the 3 semesters we worked on this project, we ended up with a team of 5 dedicated undergraduate engineering students who stuck it out till the end. This project was incredibly rewarding to work on. Not only did my technical knowledge, prototyping intuition, and design methodology strengthen over the course of the 3 semesters, my understanding of how to work in a team grew enormously. From simple face to face communication on technical topics, to delegating tasks that play to the strengths of each team member, to maintaining a unified vision, and even keeping my team motivated and inspired to pursue this project, I couldn’t have asked for a better platform to grow as a future professional engineer.

Motivation

In response to growing popularity in UAVs, drone manufacturers and developers are increasingly putting efforts into improving the performance and capabilities of their products. One of the most important metrics for multirotor performance is flight time, how long the vehicle can stay in the air before its battery depletes. The longest flight time among consumer UAVs only reach up to half an hour. Researchers across the globe are seeking to improve battery chemistries and UAV flight efficiency. The Midair Hotswap project approaches this problem from another angle, replacing the battery of a drone with a new one, without touching the ground.

Project Description

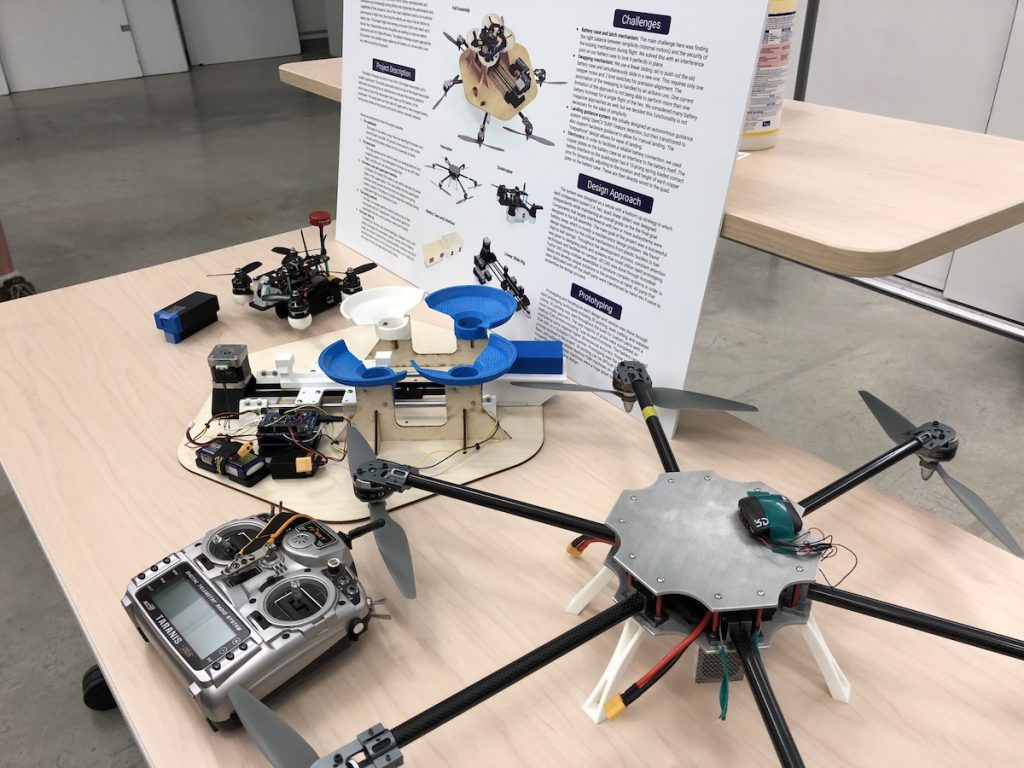

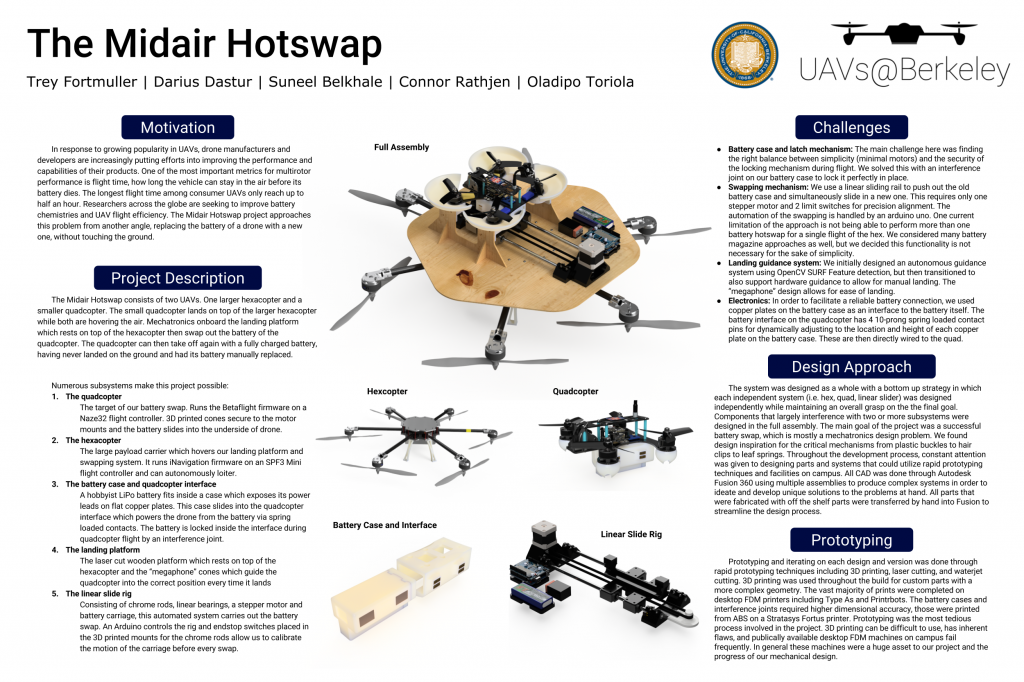

The Midair Hotswap consists of two UAVs. One larger hexacopter and a smaller quadcopter. The small quadcopter lands on top of the larger hexacopter while both are hovering the air. Mechatronics on board the landing platform which rests on top of the hexacopter then swap out the battery of the quadcopter. The quadcopter can then take off again with a fully charged battery, having never landed on the ground to get its battery replaced.

Subsystems

- Quadcopter: The target of our battery swap. Runs the Betaflight firmware on a Naze32 flight controller. 3D printed cones secure to the motor mounts and the battery slides into the underside of drone.

- The Hexacopter: The large payload carrier which hovers our landing platform and swapping system. It runs iNavigation firmware on an SPF3 Mini flight controller and can autonomously loiter.

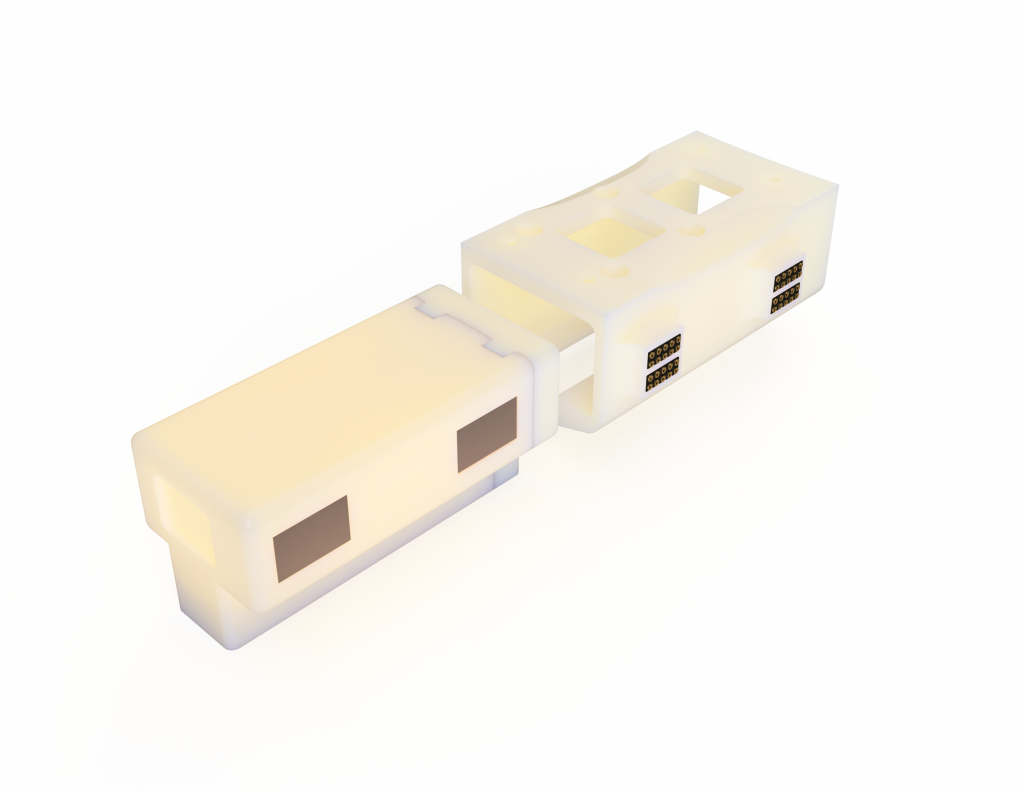

- Battery Case and Interface: A hobbyist LiPo battery fits inside a case which exposes its power leads on flat copper plates. This case slides into the quadcopter interface which powers the drone from the battery via spring loaded contacts. The battery is locked inside the interface during quadcopter flight by an interference joint.

- Landing Platform: The laser cut wooden platform which rests on top of the hexacopter and the “megaphone” cones which guide the quadcopter into the correct position every time it lands.

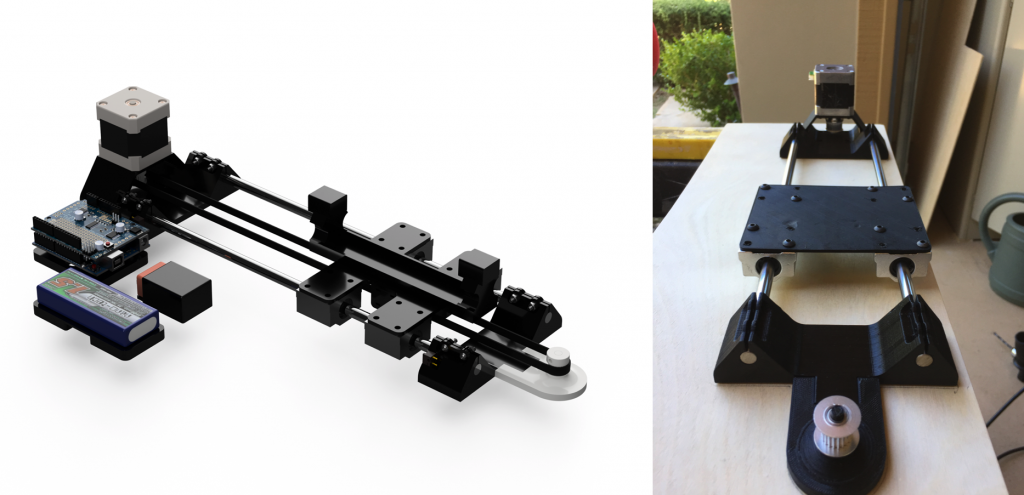

- Linear Slide Rig: Consisting of chrome rods, linear bearings, a stepper motor and battery carriage, this automated system carries out the battery swap. An Arduino controls the rig and end stop switches placed in the 3D printed mounts for the chrome rods allow us to calibrate the motion of the carriage before every swap.

Challenges

Battery Case and Latch Mechanism

The main challenge here was finding the right balance between simplicity (minimal motors) and the security of the locking mechanism during flight. We solved this with an interference joint on our battery case to lock it perfectly in place.

Swapping Mechanism

We use a linear sliding rail to push out the old battery case and simultaneously slide in a new one. This requires only one stepper motor and 2 limit switches for precision alignment. The automation of the swapping is handled by an Arduino Uno. One current limitation of the approach is not being able to perform more than one battery hotswap for a single flight of the hex. We considered designing battery magazines that carry many batteries at once but decided to skip this feature for our proof of concept. The onboard arduino runs code hosted on this GitHub repo.

Landing Guidance System

We initially designed an autonomous guidance system using OpenCV SURF Feature detection, but then transitioned to supporting hardware guidance to allow for manual landing. The “megaphone” scoops allows for easier precision landing.

Electronics

To facilitate a reliable battery connection, we used copper plates on the battery case as an interface to the battery itself. The battery interface on the quadcopter has 4 10-prong spring loaded contact pins for dynamically adjusting to the location and height of each copper plate on the battery case. These are then directly wired to the quad.

Design Approach

The system was designed with a bottom up strategy in which each independent system (i.e. hex, quad, linear slider) was designed independently while maintaining an overall grasp on the the final goal. Components that interface with two or more subsystems were designed in the full assembly. The main goal of the project was a successful battery swap, which is mostly a mechatronics design problem. We found design inspiration for the critical mechanisms from plastic buckles to hair clips to leaf springs. Throughout the development process, constant attention was given to designing parts and systems that could utilize rapid prototyping techniques and facilities on campus. All CAD was done through Autodesk Fusion 360 using multiple assemblies to produce complex systems to ideate and develop unique solutions to the problems at hand. All parts that were fabricated with off the shelf parts were transferred by hand into Fusion to streamline the design process.

Prototyping

Iterating on each design was done through rapid prototyping techniques including 3D printing, laser cutting, and waterjet cutting. 3D printing was used throughout the build for custom parts with a more complex geometry. The vast majority of prints were completed on desktop FDM printers including Type As and Printrbots. The battery cases and interference joints required higher dimensional accuracy, those were printed from ABS on a Stratasys Fortus printer. 3D printing can be difficult to use, has inherent flaws, and publicly available desktop FDM machines on campus fail frequently. Though these machines can be frustrating, the frequency with which they allowed us to iterate on parts with complex 3D geometry was a huge asset to our project and the progress of our mechanical design.

Testing

In our final test flights, the quadcopter performed reliably and the quick release electrical connection to the battery didn’t fail. The hexacopter was flown with all it’s battery-swapping mechanisms onboard. It performed well with plenty of headroom on the throttle stick despite the heavy payload of the stepper motor and linear rails. We manually orchestrated the landing of the quadcopter on top of the hexacopter while the hexacopter was resting on the ground. Considering how difficult this operation is, we did not attempt a manual landing of the quadcopter on the platform while the hexacopter was airborn. Maybe a future UAVs@Berkeley project team will work on autonomous precision landings, and will be able to integrate their work into our project and perfect the airborn swap. The final testing day is summerized in the video below.

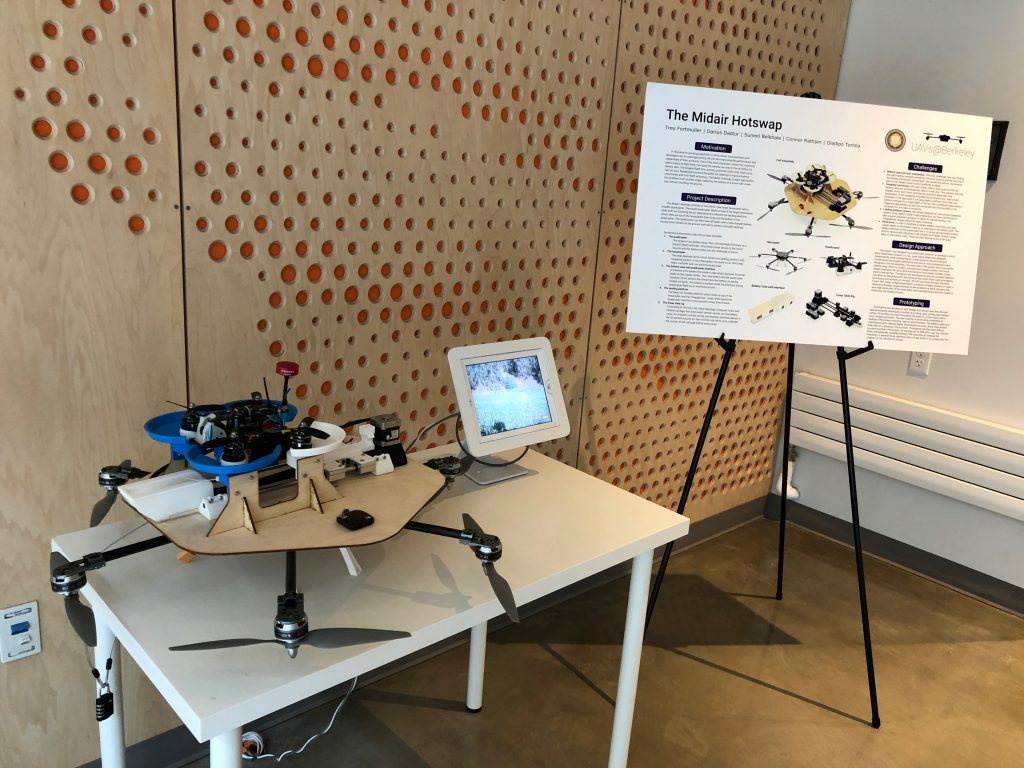

Display

The hardware for this project was too painstakingly designed and constructed to dissassemble for future projects, and was too large to store in the lab, so I looked for display options somewhere on campus. The Jacobs Institute for Design Innovation was my first stop because nearly all the custom parts for our project we’re fabricated in the building. Jacobs Hall was excited about the project and as of this writing (the Spring of 2018), the Hotswap project is resting next to our project poster and an iPad looping the video below in the lobby of Jacobs Hall. Hopefully the display will inspire future generations of Berkeley engineers and UAVs@Berkeley members to try something equally ambitious.

The Team

UAVs@Berkeley’s Fall 2017 Milestone 3 event, from left to right: Suneel, Connor, Dipo, Darius, and yours truly.

Featured Video from Autodesk

Jeff Lee is a Program Manager for Field Engagement in the Autodesk Education Experiences group. Jeff has helped UAVs@Berkeley get onboarded with Autodesk’s cross-platform CAD tool Fusion 360, which was used throughout the mechanical design of the Hotswap project. We were lucky enough to have our project featured in Jeff’s “Day In The Life” Autodesk employee profile video series, check it out: